Hanging Death of Lennon Lacy

The image of a black boy hanging from a rope is in the souls of all of us

report by Ed Pilkington

Friday 29 August was a big day for Lennon Lacy. His high school football team, the West Bladen Knights, were taking on the West Columbus Vikings and Lacy, 17, was determined to make his mark. He’d been training all summer for the start of the season, running up and down the bleachers at the school stadium wearing a 65lb exercise jacket. Whenever his mother could afford it, he borrowed $7 and spent the day working out at the Bladenboro gym, building himself up to more than 200lbs. As for the future, he had it all planned out: this year he’d become a starting linebacker on the varsity team, next year he’d earn a scholarship to play football in college, and four years after that he’d achieve the dream he’d harboured since he was a child – to make it in the NFL.

“He was real excited,” said his Knights team-mate Anthony White, also 17, recalling the days leading up to the game. “He said he was looking forward to doing good in the game.”

The night before the game, Lacy did what he always did: he washed and laid out his football clothes in a neat row. He was a meticulous, friendly kid who made a point of always greeting people and asking them how they were doing. Everybody in his neighbourhood appears to have a story about how he would make a beeline to shake their hand, or offer to help them out by moving furniture or anything else that needed doing. “He was in the best sense a good kid,” said his pastor, Barry Galyean.

His brother, Pierre Lacy, said that football was the constant that ran through Lennon’s life since he started out as a Pee Wee: “He was very serious about being a professional, very passionate about it. He never changed his mind or wavered from the course.”

But Lacy never made it to the game that night. At 7.30am on Friday – exactly 12 hours before the game was scheduled to start – he was found hanging from a swing set about a quarter of a mile from his home. The Knights had lost one of the most promising players; his tight-knit family was thrown into despair; and a question echoed around the streets of the tiny town of Bladenboro, North Carolina: what had happened to Lennon Lacy?

The last person known to have seen Lacy alive was his father, Larry Walton. Around midnight on the night before the game, he came out of his bedroom to fetch a glass of water and saw his son preparing his school bag for the following morning. “I told him he needed to get to bed, the game was next day, and he said ‘OK, Daddy’.” A little later Walton heard the front door open and close; Walton assumed Lacy must have stepped out of the house, but thought no more of it and went to sleep.

Next morning there was no sign of Lacy, and Walton and Lacy’s mother, Claudia, thought he’d gone off to school. Later that morning, Claudia noticed he’d left some of his football gear on the line, so she called the school to say she’d bring it to him before the game. She was surprised to be told that her son hadn’t turned up at school. Just as she put the phone down, there was a knock on the door, and the Bladenboro police chief, Chris Hunt, was standing in front of her.

“I need you to come with me,” he said.

Claudia was led to a trailer park a short walk from her home, where an ambulance was parked on the grass next to a wooden swing set. Even before she had got to the ambulance she saw police officers clearing away the crime scene tape that had been placed around the swing.

Then she saw Lennon’s body lying in the ambulance in a black body bag, and on top of the immense shock and grief of seeing her son lifeless in front of her, the bewilderment intensified. “I know my son. The second I saw him I knew he couldn’t have done that to himself – it would have taken at least two men to do that to him.”

She noticed what she describes as scratches and abrasions on his face, and there was a knot on his forehead that hadn’t been there the day before. In a photograph taken of Lacy’s body lying in the casket, a lump is visible on his forehead above his right eye. “From that point on it was just not real, like walking through a dream,” she said.

Five days after Lennon Lacy was found hanging, the investigating team – consisting of local police and detectives from the state bureau of investigation – told the family that it had found no evidence of foul play. There was no mention of suicide, but the implication was clear. In later comments to a local paper, police chief Hunt said: “There are a lot of rumours out there. And 99.9% of them are false.”

The Lacys were left with the impression that, for the district attorney, Jon David, and his investigating team, the question of what had happened to Lennon Lacy was all but settled just five days after the event. But it wasn’t settled for them.

As the Rev William Barber, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in North Carolina, put it at a recent memorial service for Lennon Lacy held at the family’s church, the First Baptist in Bladenboro: “Don’t ask these parents to bury their 17-year-old son and then act as though everything is normal. Don’t chastise them for asking the right questions. All they want is the truth.”

Barber was careful to stress that that truth was elusive – no one knows what happened to Lennon Lacy, he said, beyond the bald facts of his death. If a full and thorough investigation concluded that the teenager had indeed taken his own life, then the Lacy family would accept that.

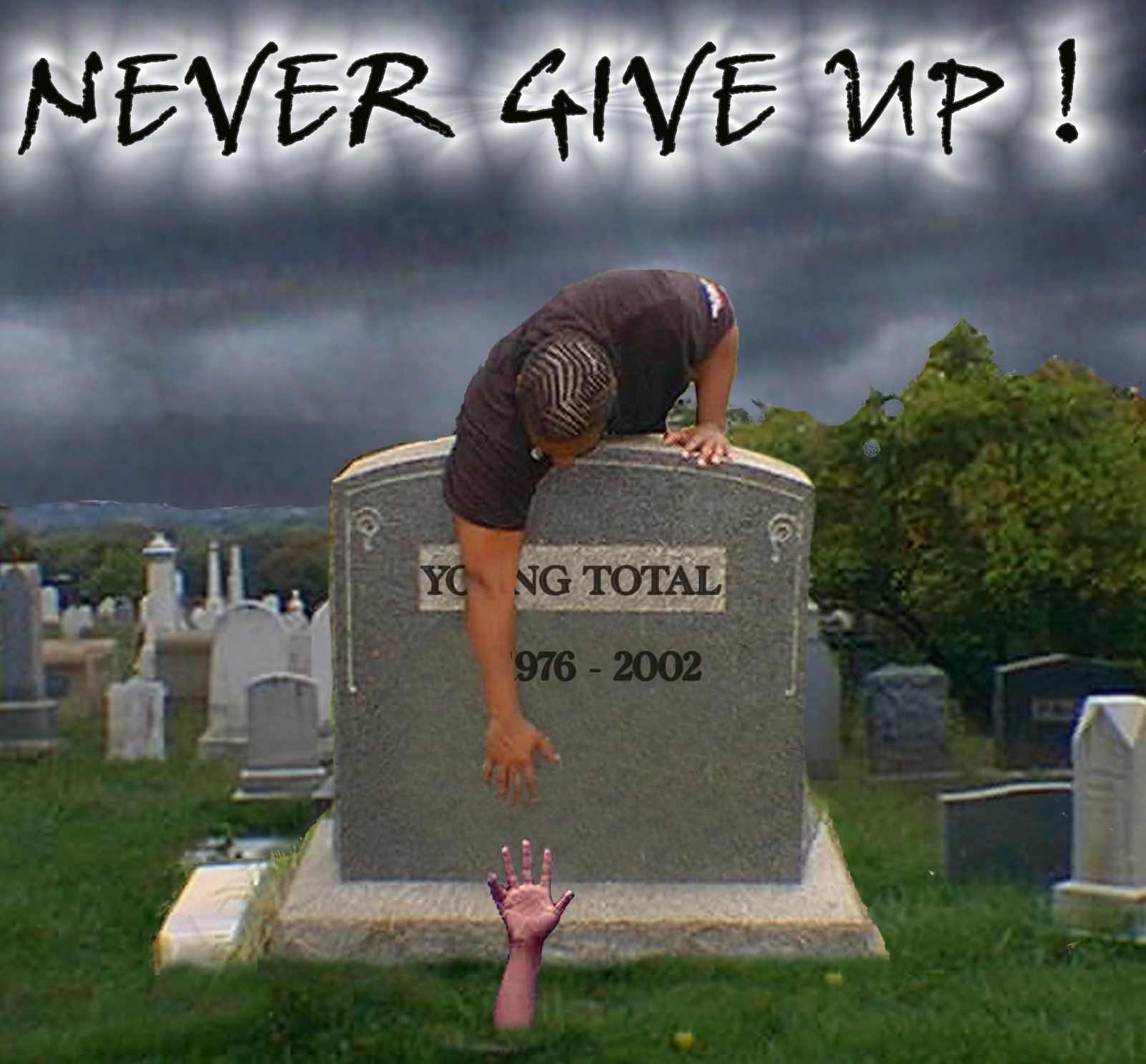

But Barber also talked about the chilling thought that lingered, otherwise unmentioned, over the scores of black and white people attending the packed memorial. “The image of a black boy hanging from a rope is in the souls of all of us,” he told them. “It is in the DNA of America. In 2014, our greatest prayer is that this was not a lynching.”

In Bladenboro, a town of just 1,700 people – 80% white, 18% black – the bitter legacy of the South’s racial history is never far from the surface. The African Americans have a nickname for the place: they call it “Crackertown” in reference to its longstanding domination by the white population.

The events of 29 August have become entangled in that historical narrative, inevitably perhaps in a state in which 86 black people were lynched between 1882 and 1968.

While America debates whether it is moving into a post-racial age, the truth in Bladenboro is that the past is very much here and now, and that the terrible image of “strange fruit” will hover over this town for as long as the truth about Lennon Lacy’s death remains uncertain.

Which is paradoxical, because Lacy had joined a multiracial youth group across town at the Galeed Baptist church where he went for weekly services and basketball ministry, and his friends were black and white, in almost equal measure.

For several months before he died, he was also in a relationship with a white woman, Michelle Brimhall, who lives directly opposite the Lacy family home. The liaison with Brimhall raised eyebrows because, at 31, she was almost twice his age. (The age of consent in North Carolina is 16.)

“Everybody was going on to me because he was 17 and I am 31,” Brimhall told the Guardian. “We told people we weren’t seeing each other so they would stop giving us trouble.”

The Lacy family said that Brimhall had split up with Lacy a couple of weeks before he died and that she had a new boyfriend. But she denied that. “We were still together, I did not break up with him,” she said. “I had never had a man treated me as good as he did, and I probably will never find another.”

Brimhall said she did not notice any hostility towards them as a mixed-race couple. But she is convinced that Lennon did not take his own life. “No, Lennon did not kill himself. He loved his mother so much, he would never put her through that.”

She added: “I want to know who did it. I want them to suffer.”

Brimhall’s close friend, Teresa Edwards, lives a few doors down from the Lacys. Edwards said that she was desperate to find out the truth, particularly as Lacy was such a good person. “For him to be black – I’m not stereotyping or anything, I’m not racist, I love everybody – but he was a very well-mannered child.”

A white couple, Carla Hudson and Dewey Sykes, live in a trailer home right behind the Lacy house. Soon after Lennon died his family learned that a few years ago Sykes and Hudson had been instructed by police to remove from their front lawn a number of Confederate flags and signs saying “Niggers keep out”.

The Guardian asked the couple why they had put up the signs. Sykes said that it was his idea. “There were some kids who ganged up on our kid and I put some signs up.” Asked whether he now regretted doing so, he replied: “Yeah, I regret it now.”

Carla Hudson said she had begged her husband to take the signs down. “I told him he had to stop that. It wasn’t how I saw things – there’s not a racist bone in my body.”

There is no evidence to suggest that either Hudson or Sykes had anything to do with Lacy’s death. Asked about the teenager, Hudson said: “Lennon was like a son to me, and this was his second home. He was nothing like the people we have trouble with. In my eyes he was just perfect.”

About a week after Lacy died, his family, with the help of the NAACP and their own lawyer, put together a list of questions and concerns that they presented to the district attorney. First, there was the overriding sense that Lennon was simply not the kind of boy to harm himself. He had no history of mental illness or depression, and was so focused on his future it was inconceivable he would intentionally cut it short.

The day before Lacy was found hanging, there had been a funeral service for his great uncle Johnny, who had died a couple of weeks previously. Lacy had been close to his uncle, and was visibly upset, but not to an extreme degree, his family said. He grieved “as a normal person would”, Claudia said.

Then there were those facial marks on his body. Even the undertaker, FW Newton Jr, who has worked as a mortician for 26 years, was taken aback by what he saw.

Newton told the Guardian that when he received Lacy’s body two days after he died, he was struck by the abrasions he saw across both shoulders and down the insides of both arms. He also noted facial indentations over both cheeks, the chin and nose. Though police have told the Lacy family that ants were responsible for causing the marks, to Newton the state of the body reminded him of corpses he had embalmed where the deceased had been killed in a bar-room fight.

The Guardian asked the local Bladenboro police department, the district attorney and the state bureau of investigation to respond to the allegation that they had conducted an inadequate investigation. They all declined to comment on the grounds that the investigation was ongoing.

In a statement posted on the Bladenboro town website, the district attorney, Jon David, said that the “victims [sic] family, and the community, can rest assured that a comprehensive investigation is well underway. All death investigations, particularly those involving children, are given top priority by my office. Investigations are a search for the truth, and I am confident that we have a dedicated team of professionals, and the right process, to achieve justice in this matter.”

David said that his team was keeping the Lacy family and its representatives closely apprised of the investigation, and had met community leaders to explain to them the current state of affairs. But he added that “to date we have not received any evidence of criminal wrongdoing surrounding the death”.

The family have many other questions that they still want answered. Who desecrated Lennon Lacy’s grave a few days after the burial, dumping the flowers 40 feet away beside the road and digging a hole in one corner of the plot? Why didn’t forensic investigators take swabs from under Lacy’s fingernails and DNA test them to see if he had been in physical contact with anybody else before he died? Have the police probed deeply enough into Lacy’s wider group of friends and acquaintances; the family were disturbed to find, for instance, that one white associate of Lennon’s had a Confederate flag as the backdrop to his Facebook page.

They also want to know why it is it taking so long for the autopsy report to come through, with still no date set for its public release five weeks after the event. So far only the toxicology report has come back, showing that Lacy had no drugs, alcohol or other chemicals in his bloodstream.

The location where Lacy was found, the mobile home park at the Cotton Mill, has also caused the family great difficulty. The swing set from which he was hanging is one of eight such sets standing in a line in the middle of a rectangle of 13 mobile homes. The spot is desolate and vulnerable, overlooked as it is by so many trailer homes, like a sports field surrounded by grandstands.

“If my brother wanted to take his own life, I can’t understand why he would do it in such an exposed place. This feels more like he was put here as a public display – a taunting almost,” Pierre Lacy said.

Lacy was found wearing a pair of size 10.5 white sneakers, with the laces removed, which no one in his family recognised. A few days before he died, he had bought himself a new pair of Jordans for the start of school year. They were grey with neon green soles, size 12, and have been missing ever since.

The family also wonders why the former husband of Michelle Bramhill and the father of her children, whom she left in February before relocating to Bladenboro, has yet to be interviewed by detectives. There is no evidence to implicate him in the circumstances surrounding Lacy’s death, but the family would still like to know why detectives have yet to speak to him.

Allen Rogers, a Fayetteville lawyer with 20 years’ experience in criminal cases who is representing the Lacy family, said there were too many questions still unanswered. “I don’t believe that a thorough investigation has been done, and within that investigation, the evidence the police has compiled is not sufficient to rule out foul play. The concern is that there’s been a rush to judgment – a desire quickly to settle any issue over the cause of death,” he said.

Rogers conceded that it was hard for any family to accept a suicide in its midst, and that it would be natural in those circumstances to search for alternative explanations, to clutch at straws. But he said that in this case the clutching at straws appeared to have been on the part of “elected officials who can’t deal with the realities of race. Given the sensitivity of the issues here, it’s much easier to put this in a box marked ‘suicide’ than ask the tough questions. I’m afraid that politics have held back the investigation.”

A few hours after Lacy’s body was discovered, the coach of the West Bladen Knights called the team together to break to them the tragic news. He asked them what they wanted to do. They voted unanimously to play on, dedicating the game to their lost brother, Lennon Lacy. They won, 57-22.

NC NAACP Requests Federal Investigation of Teenage Hanging Death

FBI Will Investigate Lennon Lacy’s Hanging Death in North Carolina

At the family’s request and ahead of an “awareness” march this past Saturday meant to drum up attention, the FBI has agreed to investigate the hanging death of a black 17-year-old high school football player. Lennon Lacy was found this August hanging from a wooden swing set in the middle of a trailer park in Bladenboro, North Carolina. Lacy’s family had requested that the feds step in after local officials ruled his death a suicide and closed the case within five days. The family, aided by the local chapter of the NAACP and bolstered by findings of their own private forensic investigation, strongly disagrees.

“We don’t know what happened to my son three months ago, and suicide is still possible. But there are so many unanswered questions that I can’t help but ask: Was he killed? Was my son lynched?” Lennon’s mother Claudia Lacy writes in a Guardian op-ed .

Lacy’s ex-girlfriend, according to CNN , was a 31-year-old white woman (age of consent in the state is 16*) and a local Klu Klux Klan rally had taken place in a nearby town in the weeks before his body was found. Some speculate that Lacy’s interracial relationship with an older white woman could be motive in this small North Carolina town.

Family still searching for answers after death of Lennon Lacy

Teen’s death brings up painful past in South

No comments:

Post a Comment